Over a year ago, Apple announced plans to scan for child sexual abuse material (CSAM) with the iOS 15.2 release. The technology is inevitable despite imperfections and silence about it.

Apple announced this scanning technology on August 5, 2021 to appear in iCloud Photos, iMessage, and Siri. These tools were designed to improve the safety of children on its platforms.

At the time, these tools would release within an update for watchOS, iOS, macOS, and iPadOS by the end of 2021. Apple has postponed since then, removing mention of CSAM detection in iCloud Photos and posting an update to its Child Safety page.

And then, the complaints started. And, they started, seemingly ignorant that Microsoft had been scanning uploaded files for about 10 years, and Google for eight.

Apple had also already been doing so for a few years, with a server-side partial implementation even before the iOS 15.2 announcement. Its privacy policy from at least May 9, 2019, says that the company pre-screens or scans uploaded content for potentially illegal content, including child sexual abuse material. However, this appears to have been limited to iCloud Mail.

Likely in response to the massive blowback from customers and researchers, in September 2021, Apple said that it would take additional time to collect input and make improvements before releasing its child safety features for iCloud Photos. It kept some initiatives going, and followed through with Messages and Siri.

Child safety on Apple platforms

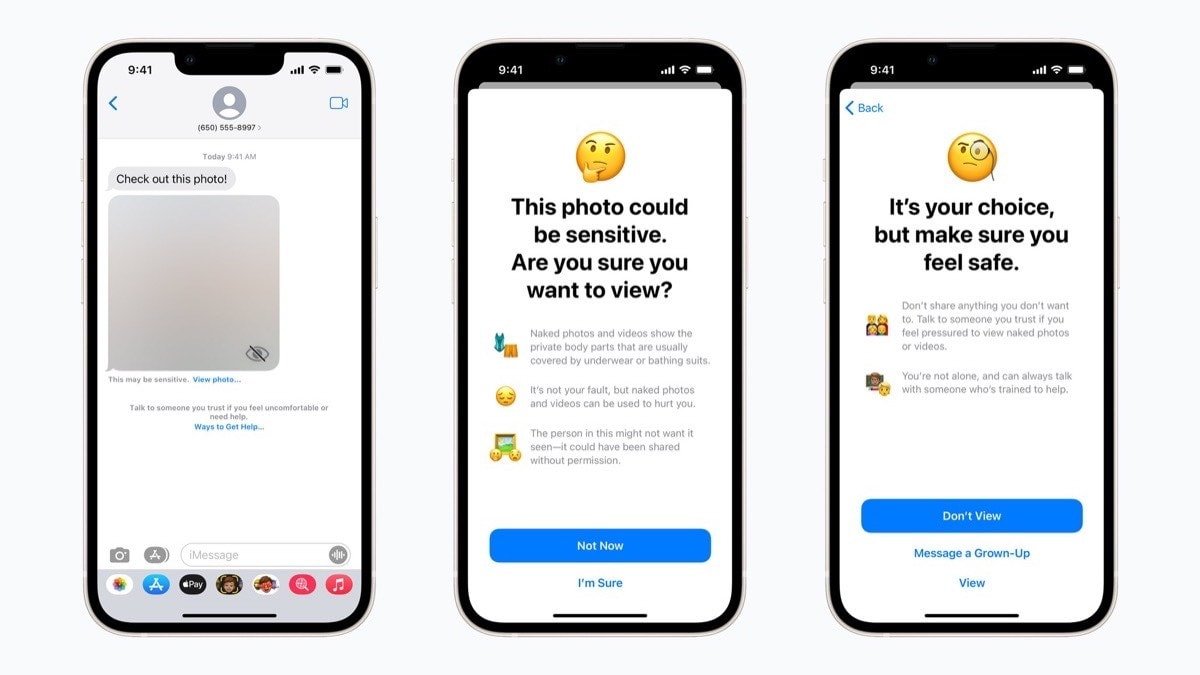

In Messages, iOS warns children between 13 years and 17 years old included in an iCloud Family account of potentially sexually explicit content detected in a received text. For example, if the system detects a nude image, it automatically blurs it, and a popup appears with a safety message and an option to unblur the image.

For children under 13 years, iOS sends parents a notification if the child chooses to view the image. Teens between 13-17 can unblur the image without the device notifying parents.

Siri, along with search bars in Safari and Spotlight, steps in next. It intervenes when an Apple user of any age performs search queries related to CSAM. A popup warns that the search is illegal and provides resources to "learn more and get help." Siri can also direct people to file a report of suspected child abuse material.

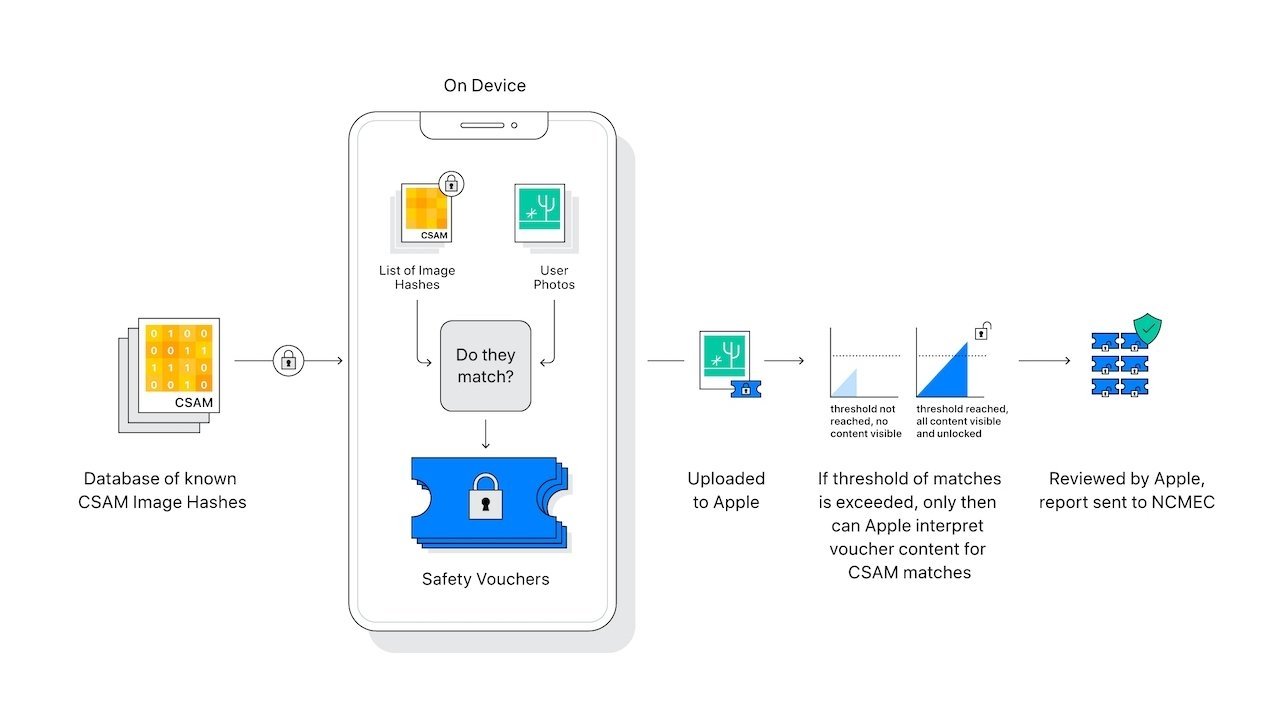

Finally, iCloud Photos would also detect and report suspected CSAM. Apple's plan was to include a database of image hashes of abuse material for on-device intelligence. This National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) database aims to ensure that Apple platforms only report child abuse material already found during law enforcement investigations.

Apple says that the event of a false positive match is rare, saying that the odds are one-in-a-trillion on any given account. There is also a human review team that makes the final call on whether to notify law enforcement or not, so the slope doesn't immediately end with a police report.

The slippery, yet bumpy, slope

The detection tools in iCloud Photos were the most controversial. As one example, an open letter penned by Edward Snowden and other high-profile people raises concerns that certain groups could use the technology for surveillance. Democratic and authoritarian governments could pressure Apple to add hash databases for things other than CSAM, such as images of political dissidents.

Indeed, the Electronic Frontier Foundation noted that it had already seen this in action, saying: "One of the technologies originally built to scan and hash child sexual abuse imagery has been repurposed to create a database of "terrorist" content that companies can contribute to and access for the purpose of banning such content."

The slippery slope does have bumps on it, however. In August 2021, Apple's privacy chief Erik Neuenschwander responded to concerns in an interview, saying that Apple put protections in place to prevent its technology from being used for content other than CSAM.

For example, the system only applies to Apple customers in the U.S., a country that has a Fourth Amendment barring illegal search and seizure. Next, since the technology is built directly into its operating systems, they have to apply to all users everywhere. It's not possible for Apple to limit updates to specific countries or individual users.

A certain threshold of content must also be met before the gears start turning. A single image of known CSAM isn't going to trigger anything, instead, Apple's requirement is around 30 images.

Apple published a document of frequently asked questions in August 2021 about the child safety features. If a government tried to force Apple to add non-CSAM images to the hash list, the company says it will refuse such demands. The system is designed to be auditable, and it's not possible for non-CSAM images to be "injected" into the system.

Apple says it will also publish a Knowledge Base with the root hash of the encrypted database. "users will be able to inspect the root hash of the encrypted database present on their device, and compare it to the expected root hash in the Knowledge Base article," the company wrote.

Security researchers can also assess the accuracy of the database in their own reviews. If the hash of the database from an Apple device doesn't match the hash included in the Knowledge Base, people will know that something is wrong.

"And so the hypothetical requires jumping over a lot of hoops, including having Apple change its internal process to refer material that is not illegal, like known CSAM and that we don't believe that there's a basis on which people will be able to make that request in the US," Neuenschwander said.

Apple is right to delay the feature and find ways to improve the accuracy of its system, if needed. Some companies that scan for this type of content make errors.

And one of those problems was highlighted recently, by a fairly monumental Google screw-up.

The problem with pre-crime

A major example of flawed software happened on August 21 with Google. The New York Times published a story highlighting the dangers of such surveillance systems.

A father in San Francisco took a picture of his toddler's genitals at his doctor's request due to a medical problem. He sent the image through the health care provider's telemedicine system, but his Android phone also automatically uploaded it to Google Photos, a setting the company enables by default.

Flagged as CSAM, even though the image wasn't known as CSAM at that point, Google reported the images to law enforcement and locked every one of the father's accounts associated with its products. Fortunately, police understood the nature of the images and didn't file charges, although Google didn't return his account access.

Google's detection system doesn't work exactly like Apple's technology. The company's support page mentions hash matching, such as "YouTube's CSAI Match, to detect known CSAM."

But as shown in the medical case, Google's algorithms can detect any child's genitals, in addition to hashes from the NCMEC database. The page mentions machine learning "to discover never-before-seen CSAM" that obviously can't distinguish between crime and innocence.

It's a big problem and one of the reasons why privacy advocates are so concerned with Apple's technology.

Moving forward

And yet, Apple's implementation of CSAM detection in iCloud Photos is only a matter of time, simply because its system strikes a middle ground. Governments can't tell Apple to include terrorist content into the CSAM database.

The delay is only due to public outcry; Apple's mistake was in its initial messaging when announcing the feature, not with errors within the detection system.

In a report from February 2022, security company PenLink said Apple is already "phenomenal" for law enforcement. It earns $20 million annually by helping the US government track criminal suspects and sells its services to local law enforcement. Leaked presentation slides detailed iCloud warrants, for example.

Apple makes no secret of how it helps law enforcement when presented with a subpoena. Examples of information Apple can share include data from iCloud backups, mail stored on its servers, and sometimes text messages.

Governments worldwide are constantly developing ways to increase online surveillance, like the Online Safety Bill the UK introduced in May 2021. A proposed amendment to the bill would force tech companies such as Apple to detect CSAM even in end-to-end encrypted messaging services. Apple would have to move this scanning to on-device algorithms to screen iMessages before it encrypts and uploads them.

Thus far, Apple has managed to fight efforts from the US to build backdoors into its devices, although critics refer to iCloud Photo scanning as a backdoor. The company's famous fight with the FBI has kept Apple customers safe from special versions of iOS that would make it easier to crack into devices.

Whether an iOS 16 update brings iCloud Photo scanning or not is unclear, but it will happen someday soon. After that, Apple customers will have to decide if they want to continue using iCloud — or move to an end-to-end alternative solution. Or, they can turn off iCloud Photos, as Apple assured everyone that the detection process only happens with its syncing service.