Apple has a monopoly on the Steve Jobs Theater

Does the European Union, the United States, or other governments need to intervene to fix potential problems in competitive markets for personal computing?

Apple's App Store, iPhone and its services including Messages are getting extreme scrutiny by governments globally. Many of those governments seem skeptical that their citizens are buying expensive things from Apple because they are better, rather than being forced to buy things from Apple that are better because they have no real choice.

Is the free market failing, and should governments intervene to fix things?

Sometimes the invisible hand needs guidance

The effort and resources that are invested in making a product generally make it better and therefore more desirable, if their results can justify the price the seller is asking.

More sophisticated customers who have very specific needs that only expensive, premium versions of a product can address — particularly in technology markets — are often willing to pay more, sometimes much more, for products they believe are dramatically better and worth the premium.

If a price tag is too high to attract enough buyers to justify its production, the seller may be forced by the invisible hand of the market to reduce its costs. This can be done by either producing it more efficiently, or by stripping the product of its most expensive but less essential or desirable features.

These rules of the capitalist market apply to virtually everything anyone might want to buy. They have historically worked extremely well to efficiently and fairly align the production of sellers with the demand of buyers.

In some cases however, a dishonest seller might offer something that, while seemingly affordable and correctly priced, might actually promise more than it really delivers. A fraudulent product may also result in extreme dangers or hidden costs to buyers, who wouldn't have bought it if they had known about these issues back when they decided to pay for it.

A monopolist seller might also gain so much control over a market that any alternatives become impossible for buyers to consider. That can eventually enable the seller to jack up their prices and defeat the very market forces that are expected to keep supply and demand in balance.

Markets alone sometimes can't correct these kinds of issues before a lot of people are injured, so sometimes a government takes action to protect society by requiring certain minimum quality standards. An authority may also make it illegal to sell a product without sufficient warnings of potential hazards, or might choose to outright ban products that are deemed too dangerous to use.

That same authority can also take steps to dismantle an abused monopoly position to reestablish a functional market.

The case against too much guidance

When governments go too far and decide that capitalism's free markets are just too dangerous and dramatically intervene with grandiose plans to solve all these problems by assigning a group of intellectuals to decide how much everything should cost and how much production needs to occur, the result is communism.

While capitalism lifted most of the world out of extreme poverty over the last century, communism famously locked nearly all of the citizens of Russia, China, and North Korea in a miserable, inescapable poverty.

The forced liberal capitalism that America and the allies of the West imposed on fascist Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan after they were vanquished in WWII resulted in vibrant, sophisticated, peaceful, and largely affluent and successful high technology countries within just a few decades.

That didn't also occur in the communist East Germany or North Korea, nor did it occur in Russia or China, where broad prosperity and advancement has largely occured in "special economic zones" where limited experiments with capitalism were allowed to occur since the '80s.

As soon as East Germany was reunited with the rest of Germany in 1990, it dramatically transformed from being a miserable backwater with crumbling public infrastructure, dutifully dredging up low quality brown coal to power a flaccid economy where the only nice things were all the monuments erected to the grandeur of communism.

East German citizens had been risking their lives to climb over the Iron Curtain to get out. Suddenly the same people and same land transitioned into a revitalized economic powerhouse that became so successful and affluent that its biggest populist complaints now focus on the problem of too many foreign people wanting to immigrate there.

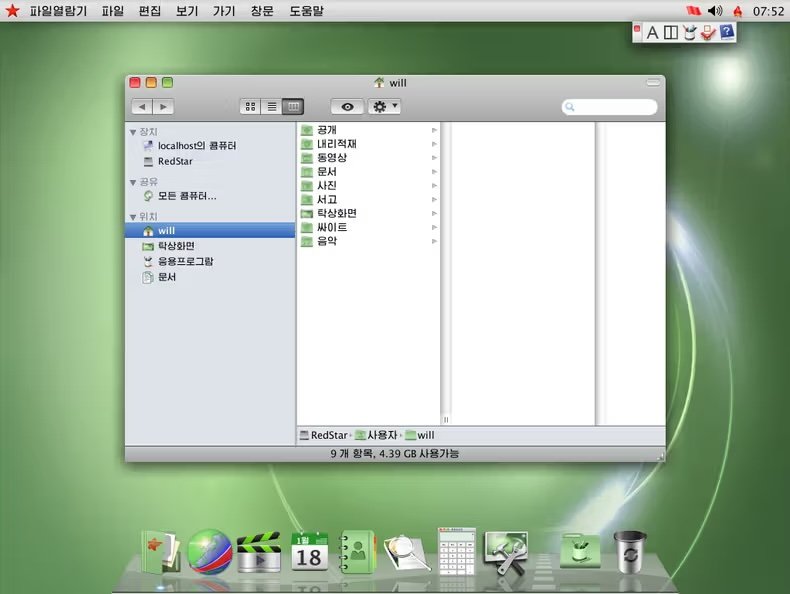

None of that occurred in North Korea, which is still forced to enjoy communism under penalty of death. Just as in Redmond, innovation in North Korea comes from imitating Apple.

Meanwhile, across the border, outside of China's wildly successful economic zones where capitalist enterprise is tolerated, the rest of the country is sitting on massive empty housing blocks of badly constructed apartment towers that were decreed to be built by its all-knowing Party intellectuals. Building everyone housing was one of the few things that communist governments were supposed to be capable of doing.

It's becoming popular for disillusioned youth in the West to bemoan "late-stage capitalism" as the reason why things are too expensive. The comparative reality of "late-stage communism" in the Russian Federation is not just inflation, but an actually fascist state that's literally tossing its youth into certain death in a monstrous war being waged in a dysfunctional attempt to annex a sovereign country that wants to be part of Russia as much as East Germany did.

While pretending no longer be communist, Russia's current leadership still imagines the solution to free markets is seizing companies' assets and dictating how they act, what they can do, and how they work. It's not working out well.

Are markets only around to lower prices?

One of the lofty objectives of communism was to provide everyone with the things they need. Karl Marx entranced followers with "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs."

Yet strident efforts to drive down costs for the proletariat resulted in products like East Germany's Trabant car, perhaps one of the worst flimsy pieces of trash ever called a "car." Never mind that actual workers had to wait years to even try to obtain one; it was a lack of any functional competition that made communist cars cheap but also really bad.

Low prices also aren't the only objective of healthy competition in free markets. For example, across much of the '90s, most PC makers offered commodity machines all defined by Microsoft's reference designs, where — outside of enterprise service contracts — virtually the only result of competition was lower and lower prices.

Those bitter price wars destroyed the viability of many PC makers in Europe and America. Somewhat ironically, it also drove all PC manufacturing to China.

While PCs got incredibly cheap, PC makers were so focused on scraping the barrel for low prices that they didn't have the ability to actually innovate. Their commodity PC products were increasingly unattractive, shoddy quality metal boxes full of various components that were poorly integrated, resulting in a frustrating, complicated experience for users, whose security was at risk and whose privacy was exploited by the ubiquitous monoculture and dreary design of Windows.

The end result: capitalist PCs weren't much different from communist automobiles.

Markets where consumers can only have cheap, low quality goods are not really functional. Should we only have one kind of cheap bananas or commodity wines in a low cost box, or one option of really cheap TV panels packaged by a variety of companies, or one car design that's super inexpensive and offered under lots of brands, but devoid of any real variety or technical experimentation?

That's the premise of Google's Android. It's given us a cheap copy of Apple's work nearly as faithfully as North Korea's Red Star OS.

Life is beautiful

We can learn a lot about how to do things by considering the greatest technology ever produced on Earth: life. The genetic variety, adaptions, and innovations of life are not adapted purely to be low cost and efficient. Life has developed over millenniums of natural selection to be fit for survival: suitability for use.

Life has developed and thrived because the genetic code corrects for errors but also allows for mutations. It's that percolation of trying fresh ideas, competing for survival and reproduction, that has enabled forms of life to adapt and thrive virtually everywhere on earth.

But while pure survival drove the peak development that resulted in our amazing dexterity, abstract capacity for thinking, and our incredible ability to learn and ponder ideas, pure survival isn't the only thing life can do. And we require lots of resources to really excel.

Farmers and people who raise animals have similarly traded off the "ability to survive in the wild" to instead breed helpless versions of plants and animals that need lots of care, but deliver other objectives: juicier fruit, meatier grains, woolier hair, fatter milk, and more consistently sized egg.

If we imagine that the only goal of free markets is to deliver cheap products, we are ignoring the incredible power of genetics to deliver life forms that aren't just efficient, they are wondrous, and usher in new worlds of possibility that wouldn't exist if life decided at some point that there should be no exciting future, just an increasingly efficient status quo.

The case against too much guidance

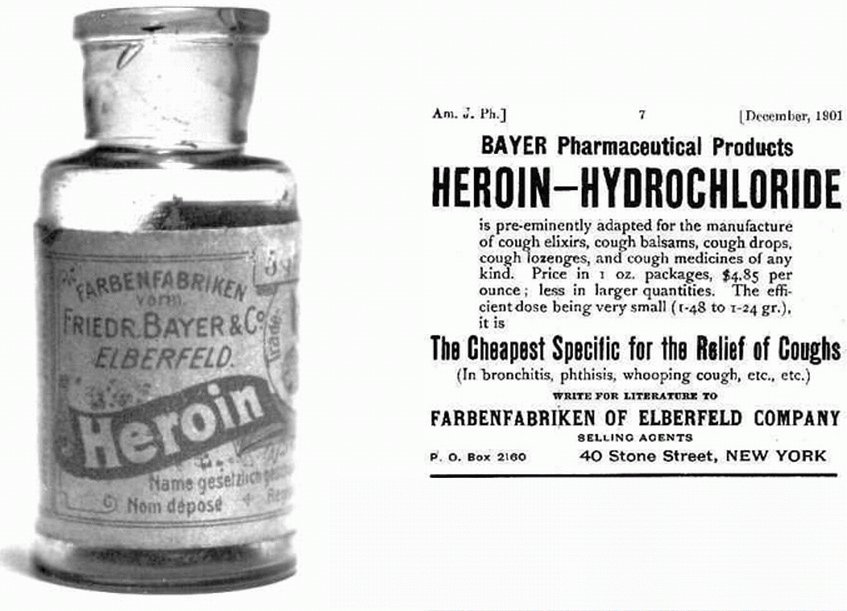

How quickly, and much action a government should take to intervene in markets to "protect consumers" involves political controversy. For example, should governments intervene in markets and ban every drug that might be used recreationally or could cause serious side effects?

Just over a century ago, Germany's Bayer pharmaceuticals produced and sold what it marketed as a safer version of morphine, with much lower addiction risk.

More than a decade after it went on sale, Bayer's trademarked "wonder drug" Heroin was actually found to be much more addictive than morphine and wildly dangerous to use, even within hospitals. Bayer lost its Heroin trademark as part of Nazi Germany's collective punishment for committing the atrocities of WWII, and the drug was eventually banned virtually everywhere.

Market forces alone didn't protect against the dangers posed by heroin. Many people who have ever used heroin across the last century felt desperately driven to want to buy it again and again at any price.

Producers have stridently attempted to meet that demand with versions ranging from pharmaceutical grade to back-alley black tar versions. But collectively, nearly everyone has since reached a consensus that heroin should not ever be freely available on the open market. It's just far too dangerous and destroys lives.

In contrast, just over the last couple decades, marijuana went from being legally classed by the Federal U.S. government as being Schedule I, as dangerous as heroin, to being viewed by a growing majority of the America population (and elsewhere) as a substance people should be able to buy if they want, even if there may be some problems associated with using it. It's not remotely as dangerous as heroin.

And across the same period of time, smoking tobacco went from being broadly tolerated nearly everywhere to being strictly forbidden by many governments from airplanes and then most restaurants and even bars. This wasn't because citizens stood up for their health rights.

Most tobacco smokers are aware it is dangerous and that it will eventually kill them. Public health advocates have successfully pushed for smoking bans because public smoking affects service workers and others who can't choose whether to be exposed to smoke or not.

As smoking bans expanded, the public has increasingly decided that these restrictions are justified. It's now almost comical to see real world portrayals in shows like Mad Men of how much everyone was smoking all the time just a few decades ago.

Smoking-related deaths are down dramatically and life spans are not just longer but more enjoyable because of much better health, both for former smokers and non-smokers who aren't forced to smoke second-hand.

Similar changes are now incrementally repealing government restrictions on the research and medical use of other formerly forbidden drugs ranging from MDMA to psilocybin to ketamine. For decades, ketamine has been regarded as a very safe, valuably essential drug for emergency anesthesia, and at the same time also a dangerous party drug that can cause its recreational users to suddenly pass out and risk serious injury — or even death from drowning if they happen to be in a hot tub the way Matthew Perry tragically died.

Yet outside of sitting a hot tub, ketamine is broadly used both medically and recreationally with minimal risk to its users. It's broadly understood to pose less danger than drinking alcohol.

Additionally, new ketamine therapies have recently been found to provide dramatic relief to many people who are suffering from treatment-resistant major depression issues. Ketamine therapy was notably helping the same Matthew Perry who later died from the use of the drug in a dangerous setting.

The government only warns people not to get in a hot tub after drinking alcohol; it doesn't ban drinking. Alcohol is also known to cause more deaths and more related injuries to both its users, and the non-users around them, than the use of many other recreational drugs that are deemed illegal, yet it hasn't been banned.

The market needed government intervention to greatly reduce the dangers posed by both heroin and smoking. Society also collectively believes that the government went too far when it took similar action to completely ban any use of marijuana and some other drugs, including the U.S. Prohibition of Alcohol that was attempted a century ago with results that were far more dangerous and devastating for society than the recreational use of alcohol itself.

Markets for technology vs. the U.S Government

In the technology world, government efforts aimed at addressing perceived problems in the market have often been just as incompetently orchestrated as its War on Drugs.

In the early '90s, a U.S. Court decided Apple's trademarked protection for its unique Mac technologies shouldn't be enforced, resulting in Microsoft being effectively awarded rights to "compete" against Apple with Apple's own technology. It's hard to see in retrospect how the government was right in that case.

By the end of the '90s, Microsoft had been repeatedly investigated by the government over concerns that it was abusing a monopoly position. In 2001, Microsoft was finally found in court to have abused its monopoly position in the market for PC operating systems, using that same "look and feel" it had been allowed to appropriate from Apple a decade earlier.

If Microsoft had originally been required to create and develop its own unique products, market competition could have allowed Microsoft's own ideas and efforts to fairly compete with Apple and others, rather than being awarded a market position that went on to cause so much perceived damage to consumers and other companies that the government felt obligated to address things again.

This time around, a change in political currents prevented any real government action from being taken in the early '00s. What was the result of the most famous monopoly position in personal computing being allowed to continue under the control of an ultra powerful company awash in cash and exercising unilateral control over PC markets globally where little real competition existed?

The direct result of a lack of government inaction to break up Microsoft's monopoly was a concerted effort by rivals to try new things in the market. Apple launched iPod and positioned its Mac as smarter, safer alternative for customers who wanted to manage their "iLife" of digital music, digital photos and digital movies.

Apple also outperformed Microsoft in retail operations and aggressively rolled out regular, dramatic macOS updates — and a new Safari web browser — that made Microsoft's comparatively glacial efforts and shoddy performance and security problems with Windows Vista and Internet Explorer look incompetent.

Apple competed with innovation, not low prices. The PC market already had low prices; it was lacking innovation.

Consumers took notice and opted to pay more for a Mac or an iPod than for commodity Windows PC and a Microsoft-defined commodity PlaysForSure MP3 player.

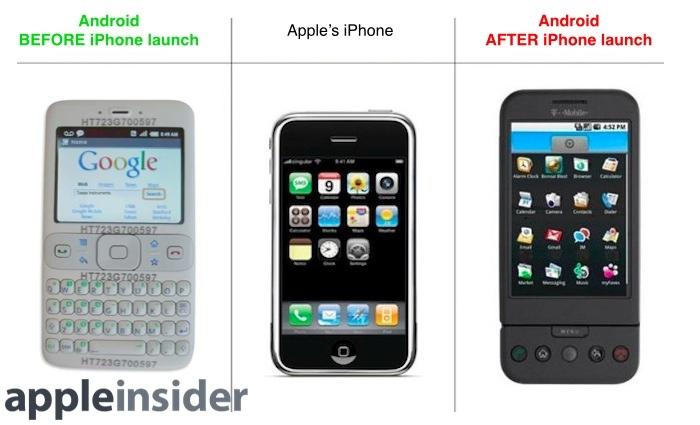

By 2007, Apple was launching iPhone to compete in an established mobile handset world that Microsoft was planning to annex into its Windows monopoly. The threat of Microsoft's efforts with Windows Mobile posed such an obvious threat to Google's search business that it, too, was hastily making plans to launch its own button-phone copy of Windows Mobile to compete against Microsoft, just as Microsoft had famously done to Apple.

Despite having a vastly smaller market position than Microsoft or Google at the time, Apple's superior work on the iPhone immediately deflated the tires of Windows Mobile and Google's original plans for Android.

Microsoft wasn't forced to buy Nokia, despite what the Department of Justice seems to believe.

Better tech at a higher price

Priced at $450 and $600, the original iPhones were obviously capable of delivering better technology and a better experience for users than the $150 Windows Smartphone handsets Microsoft was hoping to dominate the mobile world with. The question was, who would pay that kind of premium, even for a much better phone?

Microsoft's CEO Steve Ballmer — certainly no idiot in terms of understanding the value of numbers — famously laughed at Apple's potential prospects for finding any significant numbers of iPhone buyers. Industry analysts adamantly insisted for years that Apple's iPhone needed to reach a price point around $300 before it could be expected to achieve any real mass market success.

I don't have to tell you they were wrong.

Google rapidly shifted Android from being a Windows Mobile clone to being an iPhone clone. But Google also believed that mobile makers worldwide could achieve success primarily by reaching low prices, even if that meant ditching the performance, esthetics, and sophistication of Apple's iPhone.

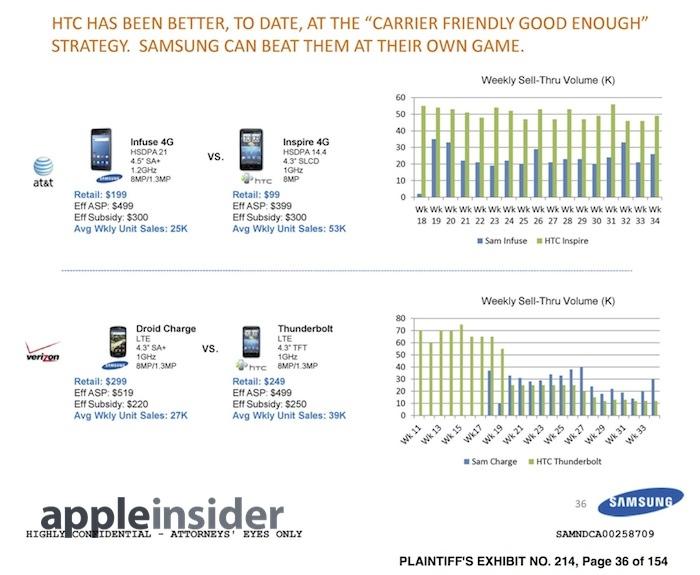

Android and its licensees — notably Samsung — aimed to produce what they called "good enough, carrier friendly" commodity crap phones that borrowed quite liberally from Microsoft's '90s strategy of Windows Everywhere via cheap commodity PC hardware.

This time around, the PC would just be smaller and have more ads.

Real competitive markets are competitive, not just cheap

Across the last decade and a half, it's clear that open competition — not government action — was driving the mobile industry to a new level of sophistication, with a broader array of options and a wider range of technological experimentation than had ever occurred under Microsoft's control of PCs.

But that vibrant new competition didn't happen because the government had stepped in. It occurred because it hadn't.

Had Microsoft been forced to break up a few years before Apple could launch its iPhone, consumers, PC manufacturers, and software makers would have all be distracted with the government's Five Year Plan efforts to split apart multiple layers of Microsoft, making the whole industry a bunch of baby Microsofts.

What if Google had snatched up a newly spun off Windows Mobile instead of acquiring the competing Android project in 2005 and launching its competitive bid to take on Microsoft with an open source strategy?

It's very likely that Apple's iPhone, today's modern Android based on it, and the vibrant competition of ideas between Apple and all the major overseas phone makers would never have existed. We'd have a Google-branded, really cheap, Microsoft-designed, "carrier friendly, good enough" mobile phone option delivering the devoid innovation of the 90s commodity PC.

No thanks!

Or what if Google had acquired a newly spun off Internet Explorer and cemented it as the world's only browser for search, rather than lending its market position to a fork of Safari in 2008 as the Chrome web browser, introducing diverse new ideas into the market?

In the market for web browsers, it's the vibrant competition for ideas that has delivered the rich technical, aesthetic, performant, and functional advancements of the web. All this competition occurred in a market where every browser was free.

Competition in markets, like competition in genetics, isn't solely about money. It's about innovation and trying new things.

And what if Google had merged with a liberated Microsoft Office business segment, rather than resorting to buy up an alternative project in 2006 that resulted in its web-based Google Docs and its subsequent web-based Office competition? Perhaps AJAX wouldn't have ever taken off for anyone.

Such acquisitions aren't hard to imagine. After all, the U.S. Government allowed Facebook to buy Instagram.

Not breaking up Microsoft was ultimately one of the smartest things the U.S. Government ever decided to do. Microsoft's monopoly power seemed to be a terrible problem back in 2000, but it was that very terror that encouraged market participants to defeat the Tyrannosaurus rex, by offering innovative, novel ideas that competed for attention.

Some innovations, like Apple's, raised prices while delivering better products. Others, like Googles, shifted costs to advertisers, distorting the simple forces of supply and demand and market choice by making consumers the product and shifting the market to serve the needs of advertisers rather than end users.

We didn't end up with another monopoly; we ended up with the richest array of diverse choices personal computing has ever seen.

Better not to interfere with competitive markets

Microsoft's iron grasp on personal computing was ultimately challenged by a better alternative product that wasn't just trying to be cheaper. It was trying to be better.

Apple's iPhone was based on better underlying technology derived from better engineering. Apple invested in better technical foundations that made it work better, delivered refined usability that expanded its ease of use to broader and newer markets, had better universal accessibility that made it useful to more people, and delivered objective beauty and aesthetics from its hardware to its UI that make it attractive and desirable to larger audiences.

If Microsoft had been broken up, rather than getting "better" things, we'd just have worse integration between the Windows PC, its Office software, its IE browser, and perhaps new issues with trying to connect a Windows A home PC created by corporation A to a Windows B enterprise server developed by corporation B.

No thanks, Janet Reno!

What if the U.S. had broken up IBM into a bunch of baby IBMs back in the early days of computing, when IBM controlled business machines internationally? Perhaps it would have driven all PC innovation overseas generations earlier.

Or perhaps we'd all still be using green screens attached to mainframes, just with less integration between them, and Silicon Valley would still be an orchard. Who would want to live in the dystopia imagined in the film Brazil?

Perhaps devoid of vibrant competition in PCs back in the '80s, America would not have had any role in creating PCs and Internet. Instead, Europe's bureaucracy would have slowly delivered global computer networks in the model of the United Nation's International Telecommunication Union standards as the world was planning to do, right up until America delivered the Internet Engineering Task Force as an open, faster, better, and more vibrant market for Internet ideas based on their technical merits, not on bureaucratic discussions.

Also remember: the AT&T monopoly that U.S. government broke up into baby bells in the early '80s— which seems in retrospect to have been correct — was fixing a problem the U.S. created when it granted AT&T that monopoly over a century earlier.

AT&T didn't become a monopoly inside of a functioning, competitive marketplace by delivering the best products and services. It was a government invention, like the Postal Service or Amtrak. It was created to service a utilitarian need that no competitive market could be expected to deliver.

The U.S. government didn't create iOS or the App Store. Seizing Apple's platforms to ensure that the company that invested to create them can't run them isn't inducing competition in order to lower prices, it's just reducing the range of options consumers have available to them.

Consumers have voted with their dollars. What they have chosen in the U.S. — and virtually everywhere else where people have any financial autonomy to choose — is not the cheapest handset subsidized by ads with backdoors to monitor their activities.

Everyone clearly wants a premium phone with an advanced camera, paired with privacy protections, controls over surveillance advertising tracking, limits on what personal data developers can access, and the security of encryption that prevents totalitarian governments from monitoring their words.

Even Android users want an iPhone, they just want it with a Google logo.

Cracking open Apple's platform and destroying its business model doesn't increase competition and innovation; it shuts it down. If Apple ever gets to some point where there's a clear need to offer a better alternative, the market will deliver one.

It did before.