Apple's CEO Tim Cook

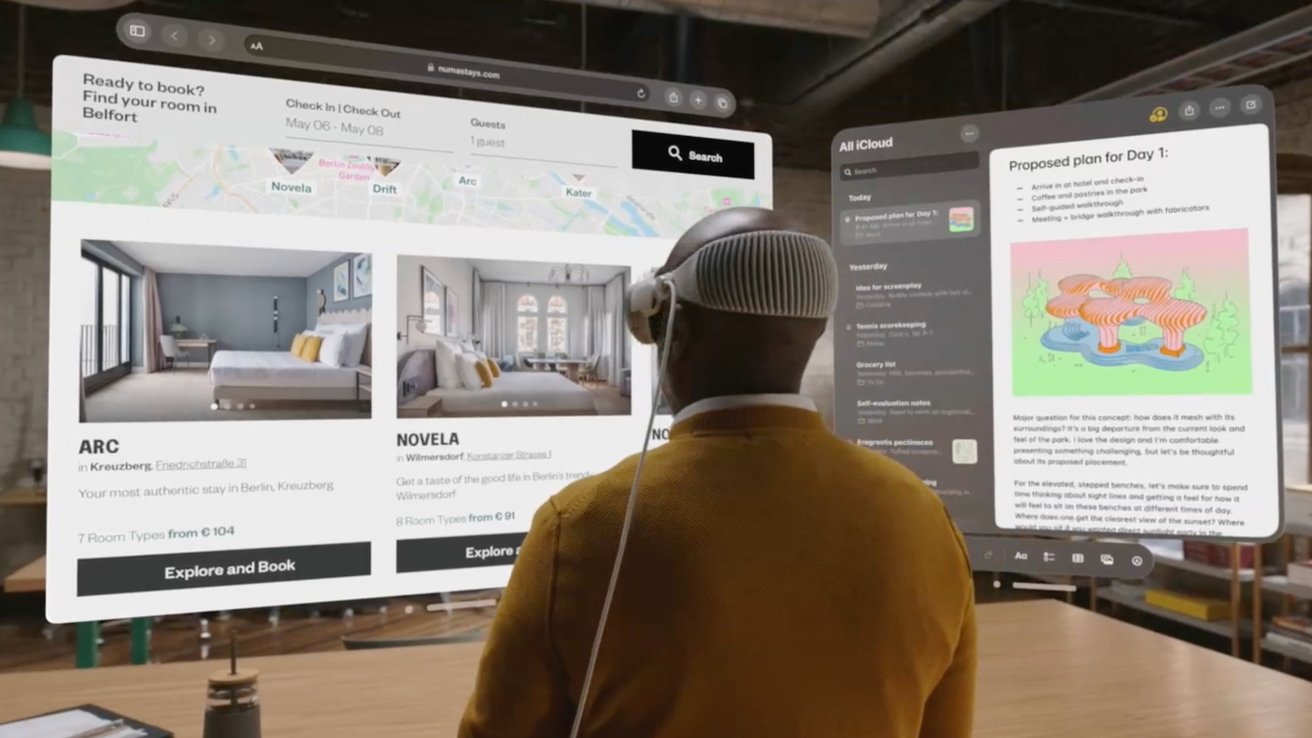

Apple demonstrated its Vision Pro at WWDC 2023, and a lot of concerned talk immediately developed centered on how well the company could deliver this ambitious product, and convince the public to buy it. Tim Cook has a vision, and as always, looking backwards to see what's worked and what hasn't paves the road to the future.

In November, I wrote "Can Apple Vision Pro reinvent the computer, again?" to review how Apple had uniquely launched its previous leaps and bounds in consumer electronics. From the original Mac to iPod, iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch, the company didn't just rush a singular, promising technology or a barely formed concept to market before its competitors could.

There are striking parallels with the upcoming launch of Vision Pro.

Three killer gasps

When they aren't writing about Apple, tech journalists like to identify the singular hot new technology that promises to bring "innovation" into an existing product category. This makes for a simple, easy to tell story.

They're almost invariably wrong afterwards. Still, they hold on to their whip and continue using it until long after the dead horse they pretend to love riding has dried up and blown away.

OLED displays and keyboards that fold or convert into something else. 3D glasses and Virtual Reality headgear. Cryptocurrency blockchains and NFCs. They demand to know, "where is Apple in all of this industry-wide handwaving?"

Then they eventually forget all about whatever they were proselytizing and move on to the next wave of hype.

Endless waves of completely convinced, doe-eyed technologists nodding along excitedly to whatever public relations fantasy they've just sat through suddenly become rigorously skeptical when the company on stage is Apple.

When presented with more than just one new emerging technology, in a way that isn't unfinished and still conjecture, delivered alongside a carefully crafted marketing message that doesn't make use of their own faith or creativity and offers little room for distinguishing verbiage in crafting one's own narrative, they grow sour.

I watched this phenomenon from a distance across Apple's history of Macs and iPod, then witnessed this first hand behind the scenes with Apple's launch of iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch. Even the writers who specialize in talking about Apple strain to deliver an unconvinced skepticism riddled with doubt every time the company has served up the next big leap. Can't look too "faithful," that would be disingenuous! And yet when the subject is some other company — with no track record of major success — a zombified credulity reappears in their eyes.

It's as if technologist writers are the proverbial goth kids in high school, unhappy about anything bringing happiness but happy about anything dreary and miserable. "Oh no, Apple eviscerated the open markets for mobile spyware with its dreadful App Store, but hooray, here's two more messaging clients from Google I can't wait to sign up for and figure out!"

Three killer acts

Once Apple successfully launches a hit blockbuster, it then revisits its new creation generally every year, incorporating new technologies and features in a new hardware update and in a platform-refreshing major software release. No other company even comes close to Apple's level of continuous advancement. Not even the competitors sitting on monopoly market share or who singularly control the world's advertising, or who are isolated from the rule of law by their sprawling chaebol or tight party ties to the dictator running all the factories even make an attempt to maintain any notion of parity with Apple efforts.

Compare the downright lazy developmental pace of even the humongous Windows or Android platforms, paired with the Surface, Pixel, Chrome, Galaxy, Honor, Fire, and other assorted hardware branding efforts, with the relentless advancement detailed every year at WWDC and at Apple's public events held multiple times annually

It's as if the competitive race is just pretend, and that none of these other kids have to even try because they're not really goth at all, they're the spoiled rich kids who never face any consequences because their dad really earned his wealth through surveillance advertising or his party loyalty and competition is just a ruse.

In between dutifully delivering its annual updates of the world's top computing platforms, Apple is also always focused on developing some effective new solution. It then invests significant efforts to bring this to market while partnering with third parties to ensure there will be a healthy ecosystem of apps, media and accessories available.

In parallel, it develops captivating and convincing marketing to communicate the new platforms' value to interested buyers.

It's these overlapping Venn diagram circles of essential work that are all collaborating together to develop an attractive experience of a product platform, which end users and partners wanted to invest in. From that perspective, it's really not so hard to understand why this only happens at Apple.

Two weeks ago, I again outlined, from another perspective, this same essential notion that "the reality of Apple's ongoing success is incremental progress through massive ongoing investments in dreaming up what valuable solutions it can create, how to communicate this value to buyers, and who it can work with to help it deliver this."

Three killer apps

Last week, I specifically examined how the vaunted legend of the "killer app" played into this process. Once expected to be a magical unicorn that rode into a manufacturer's market and graced it with The Software Title that would sell hardware boxes like crazy in the model of VisiCalc in the 1980s, I tried to outline how the once legendary killer app has morphed and expanded into interrelated areas of critical functionality centered around media, communications and networked apps.

That's essentially how Steve Jobs introduced iPhone back in 2007. He introduced it not as three different things, but all in one!

When Apple Watch appeared in 2014, the company again emphasized its ability to deliver wireless music, to work as a phone and deliver messages, and to run an array of apps, specifically "comprehensive health and fitness apps that can help people lead healthier lives."

Similar to iPhone, which evolved as a platform in some ways Apple couldn't have predicted, Apple Watch also developed additional roles as a navigator, with glanceable notifications, Continuity unlocking, lifesaving Crash Notifications, and the simple but essential Find My Phone.

Three killer asshats

Recent decades of Macs, iPods, iPhones, iPads and Apple Watches demonstrate how Apple's platforms keep pursing a nonstop pace of innovation even as media pundits insisted the company "can't innovate."

Where was iPhone's BlackBerry keyboard? Why can't iPad fold up into a strangely fat Samsung phone? Why can't you draw on MacBook screen or touch on an iMac display or tilt the screen into a drafting table like they were built by Microsoft? Where's the essentially important round Apple Watch like Google keeps trying to evangelize?

Let's have a moment of silence for all these flops that the same crowd of media pundits bet their credibility on as being the lethal innovations that would drive sales, entice users, and excite platforms.

Three killer assets

Of course, there are also some features and ideas that Apple floated for its blockbuster products at their introductions that didn't really materialize as expected. Apple's 3D Touch phone screen lasted about as long as Samsung's rounded Edge display. iPad debuted iBooks as if it would be the iTunes of reading, but it only turned out to be Apple's Kindle. The original Apple Watch initially hailed Digital Touch as "sending something as personal as your own heartbeat," but it seems nobody saw that as being terribly useful.

Jobs once tried to peddle iPod Socks and rolled out the iPod HiFi. This year's not-so-fine-wearing FineWoven seems to have failed to displace much interest in actual cowhide iPhone covers.

The thing is, when you fall down on stage you don't need to apologize or wave your hands. You just recover, keep going and move on. Many releases of macOS, iOS and watchOS have shed less-useful features to make way for new and more valuable ways of doing things.

Apple's demonstrated platform resiliance, along with the ability to keep refocusing on delivered value and discovering new solutions for its users and partners, will also be essential for the immersive computing world being ushered in by Vision Pro.

Three killer aspects

Some of the issues Vision Pro critics have jumped on actually demonstrate the remarkable thought that's been given to subjects on Apple's end. Is it terrible that the new headset incorporates your prescription glasses into its design? I don't think so at all. If you're already paying $3,500 to join the first generation of Apple's immersive computing vision, you'll want to be able to see all of its resolution clearly.

Customizing your Vision Pro headset to your eyes creates a heightened feeling of ownership, something akin to having a personal car that you don't share. Apple Watch similarly is designed for an individual user and customized to their preferences in size and band style. Making your Apple device your own — with your own taste in a protective case, or perhaps with stickers on the case, are a key aspect of emotionally bonding you with your gear.

The first thing I did when I sprang for a PlayStation VR a few years ago is fiddle around with trying to not wear my glasses with them on, then putting them over my glasses as it says to do. My lenses immediately made a scratch on Sony's inner glass that I couldn't polish off, leaving a distracting scar right in the middle of my experience. This is a cheap way to deliver a bad experience. Apple offers an expensive way to make a delightful experience, and this has proven to be so much more commercially successful, over and over throughout its history.

A second imagined flaw with Vision Pro is its external battery on a leash. Yet the alternatives to this would be worse.

Imagine a heavy headset that incorporated all the weight of a significant battery, making you that much more top-heavy. Or simply limiting the useful session life while working in immersion because some whiny critics don't like cables or dongles or whatever they like to complain about.

Thirdly, what about wearable comfort? Apple's a technology company that sells devices and tends a marketplace of apps and accessories. It's not an apparel company.

I once had the chance to ask Jobs why Apple Stores weren't offering an array of t-shirts and other wearable branded merch. His answer was basically that he didn't want the company's retail Genius workers to be busy folding up piles of clothes.

That answer also solved a deeper question I hadn't thought to ask — should you really stretch to do things you're not that good at, particularly if they have limited value? Charlie Munger famously said no.

So does Apple.

I've already poked fun at iPod Socks and FineWoven, but Apple actually has quite successfully grown outside of its core competency in retailing well-thought out computing devices it floats on a rich platform of expanding third party functionality. And I don't just mean Services.

While much of Apple's strong vision for hit devices can be attributed to Jobs' keen sense of what people would want from a premium piece of technology hardware, the last decade of Apple has given us a clear look at what an operational genius who happens to also be Apple's gay CEO would deliver: technology as fashion.

Apple Watch, often noted as Tim Cook's first original shot at moving the company onward after the passing of Jobs, was initially criticized as a purely ornamental and unessential technology product that would never have the impact and sales of iPhone, as if that was some sort of really intelligent observation to make. The Bloombergs and Googlerati couldn't stop laughing at why a digital watch band couldn't just as well be $150 or even $13 if you just want a piece of rubber counting your steps, mostly.

But the reality has been that Apple Watch, fusing the allure of higher-end mechanical watches as a fashionable accessory with the functionality of a really powerful, bit mapped, wireless computer that can vibrate secret notifications, find your phone for you, help you get fit, and perhaps even save your life after a crash. This wasn't just a watch, it wasn't just a wearable band — it was an experience that made you feel elegant and sophisticated and it could do things of significant value for you.

Having witnessed the birth of Apple Watch and its progression through a series of partnerships with luxury band makers, Nike's sporty band partnership, and Apple's own foray into entirely new territory with Milanese Loop and up to today's Ultra bands for the rugged outdoors, I have to say I've never seen a tech company pull off real fashion before. Apple nailed it.

It now sells fashionable accoutrements that are often more expensive than the wearable computer you pair them with. Many Apple Watch bands are more expensive than what analysts thought would be the sweet spot for a mass market smartphone, or a generation prior, are pricier than what a cheap PC netbook or tablet was supposed to cost.

Apple Watch's eye for fashion and style erected a halo over the company's other products, creating a soft place for the fancy iPhone X to land a few years later. The cranky media complainers spent years blubbering about how absolutely nobody could afford a $1,000 phone (cue Ballmer laugh) and yet here we are.

And it's not just a phone, it's a $2,000 camcorder and a pricey DSLR-equivalent for the masses, and it serves as the computer you have on you when your laptop is out of reach. Apple had to make shelf space for an even fancier Pro version because we desperately wanted to pay even more once we saw what that could deliver.

MacBooks have similarly developed from their origins as plastic econoboxes into sleek, svelte precision devices crafted from rigid aluminum alloys. Throngs of customers are not rushing to leave Apple so they can strap on a rubber wearable tracked by the PRC that costs as much as a Happy Meal, even if major newspaper staff writers and not just a few market researchers claimed that would occur. iPad wasn't outsold by bargain bin cheap netbooks, or Android tablet licensees, or Google's Chrome-branded low end laptops as Bloomberg repeatedly tried to convince us would happen.

The world is better because Apple convinced us to pay more for nice stuff, rather than making do with some cheap flimsy "carrier friendly, good enough" e-trash. And so it is that Apple's next stop on this path takes us into a more intimate, immersive experience where personalized comfort and customized finishing is even more important to deliver a delightful experience.

I hope they can make enough.