Steve Jobs unveils the original iPhone which had an ARM processor

Apple investing in ARM shares is a good buy for the company, but it's bought before. When it did so in the 1980s, ARM proved to be Apple's life saver.

ARM has now filed for its initial public offering (IPO) with the SEC, a public offering that was previously threatened by China, and also by the UK. Those countries may have made the IPO seem unlikely at times, and perhaps it was never certain that Apple would invest, but there was never any doubt that Apple and ARM would continue working together.

Just to prove it, ARM's IPO filing specifies that it has a new long-term agreement with Apple. What the filing doesn't cover, because it doesn't have to, is that Apple was there in some of the earliest days of ARM thirty years ago.

Where ARM came from

ARM's processor designs are now in every iPhone, every Mac, and so much more, but originally it was created by a small British firm called Acorn. In the early 1980s, Acorn partnered with the British Broadcasting Corporation to create what became the beloved BBC Micro.

The success of that made it possible for Acorn to make longer term plans than just the next microcomputer. So the Acorn RISC Machine project was started in 1983.

RISC is short for Reduced Instruction Set Computer, and at the time just about everyone else was using what would later be known as CISC, or Complex Instruction Set Computer. RISC isn't as fully-featured CISC, so firms ignored it, but Acorn saw that what RISC can do, it can do much faster than CISC.

So RISC might be slower at some functions CISC can handle easily, but on balance it created a processor that was much faster and used much less power. That made it ideal for the then burgeoning mobile device market.

In the late 1980s, that combination caught the attention of Apple, and it began working with ARM. on November 27, 1990, Apple, Acorn and VLSI Technologies jointly formed a new firm called Advanced RISC Machines Limited.

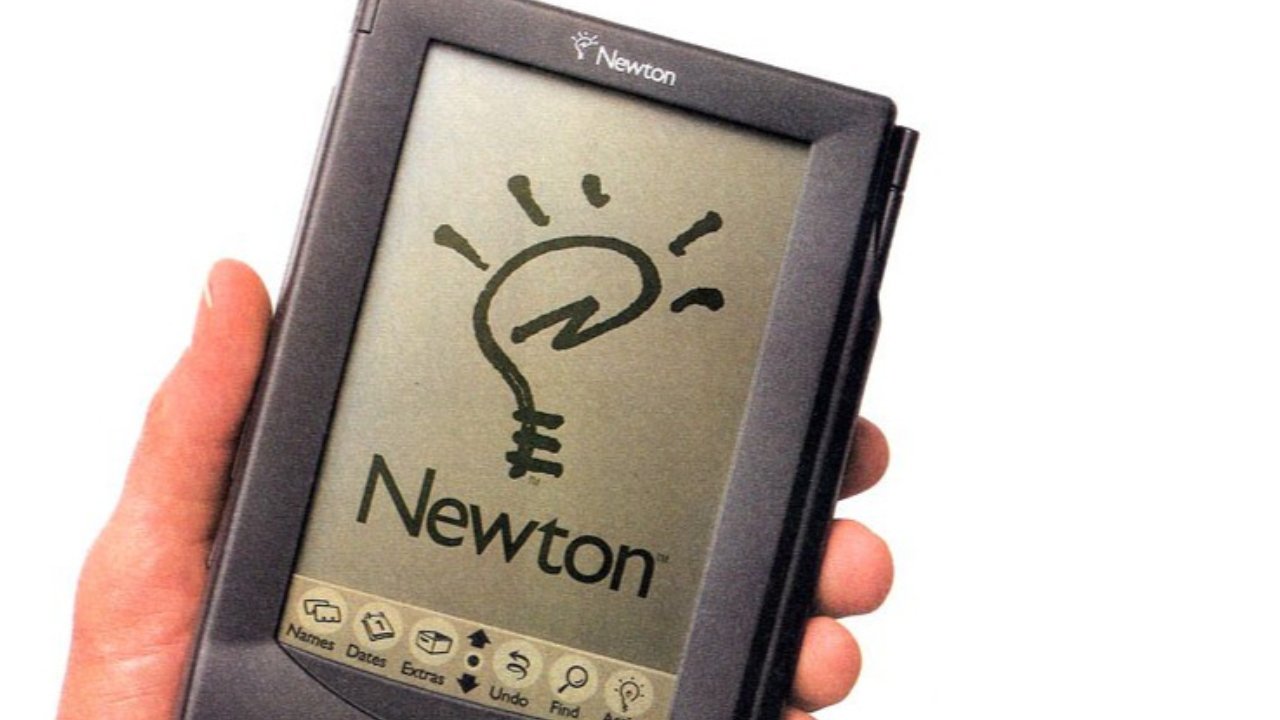

Apple invested $3 million to own 43% of the company. That investment was specifically to fund the design and development of the ARM processor for what would become the Apple Newton MessagePad.

But once that first Newton was released in 1993, ARM began looking at expanding to avoid over-reliance on any one or two customers. In what was then considered unusual, ARM began licensing its technology.

Texas Instruments became a client later in 1983 and that firm then persuaded Nokia to do the same. Very soon, ARM became what it is today — a firm that designs processors which other companies like TSMC then manufacture.

Apple pulls out

Usually it's that people who had shares in Apple and then pull out, only to regret it later. This time, though, it was Apple that sold its shares.

It's interesting to speculate what would have happened if Apple had retained its 43% ownership. Perhaps by now Apple would have completely acquired the firm — it was rumored to try in 2010 — and no one else would be using ARM designs.

But what is much more certain is that it Apple had not sold its shares in ARM, there would not be an Apple today.

It's not clear just when Apple sold shares, but it is known that it took place over some time — and that it started when Steve Jobs returned to the firm. And it is also known that by February 1999, Apple was down to owning just 14.8% of ARM.

Plus it's on record that Apple made a total of $1.1 billion out of selling those shares, which represented a profit of 366 times its original investment. That money helped Apple survive, and Jobs decision to cut the Newton — with its ARM processor — was also part of the surgery needed to keep Apple alive.

So while the Newton was a failure, and while Apple now owned progressively little of ARM, the little processor design firm was directly responsible for the saving of Apple.

And then it did it again.

Intel's mistake

When the iPhone was being developed in the mid-2000s, Apple had transitioned from PowerPC to Intel processors and the two companies seemed inseparable. So much so that when Apple wanted a processor for the iPhone, there was no question who it would go to.

So it did. Apple asked Intel to manufacture the processors for the iPhone — and Intel said no.

Today that sounds like an insane thing to do, and doubtlessly Intel would be in better shape if it had agreed. Intel might still be in use in the Mac, and certainly ARM would be ticking over as an generally unheard-of firm.

Yet at the time, Intel's decision was not wrong. At the time, Intel's expectation for the iPhone was much the same as any other industry source who knew of it — they predicted it would sell only in limited numbers.

If that had been true, then the cost of developing the processor was unlikely to be covered by the potential sales earnings.

Curiously, at the same time, Intel had just sold off its own RISC division, which had been using ARM designs.

It was only following Intel's rejection that Apple turned to ARM. Now that seems like the best outcome, but again at the time, there were reasons to see it as a compromise.

Specifically, the first iPhone was slow and it was slow because of its processor — or rather the design of it.

Fast forward a few years to the launch of the iPad, and more than the iPhone having become an unparalleled success, Apple had learned how to design processors.

You can't fail to learn when you've been iterating through one hit version of the iPhone after another. But then Apple was also hiring in expertise.

ARM keeps saving Apple

If selling ARM shares in the 1990s saved Apple once, and then buying ARM for the iPhone saved it again in the 2000s with the iPhone, it's continued to do so in the 2010s.

This time the saving of Apple has not been over a specific moment like the shares or the launch of the iPhone. Rather, working with ARM and designing its own processors, is arguably what has kept the iPhone from being outperformed by Android.

It's a truism that a flagship Android phone can have better specifications on paper than an iPhone, yet the iPhone always wins on performance.

This was especially so in 2013 when Apple released the iPhone 5s with a 64-bit processor. "This is the first-ever [64-bit processor] in a phone of any kind," said Apple's Phil Schiller at the time. "I don't think the other guys are even talking about it."

They weren't. Initially, the reaction of rivals was to mock Apple for believing any phone could need the speed and performance of a 64-bit processor.

And then they all moved to 64-bits too.

Enter Apple Silicon

Presumably Apple was disappointed when Intel said no to making the iPhone processor. But it was certainly disappointed later when Intel, despite promises, was falling further behind its own road map for producing faster processors.

Apple got into the peculiar situation where its phones on ARM were far ahead of any competitor, but its Macs were not.

In retrospect, it seems obvious that Apple would move from Intel processors in the Mac to using its own ARM designs.

Given the radical success of Apple Silicon, now it of course seems obvious that Apple will stay with ARM. That doesn't mean Intel won't keep hoping Apple will change its mind, and probably won't stop trying to get Apple users to change theirs.

But today ARM means Apple is making Macs that are better than it could ever have hoped with Intel. Today ARM means Apple's iPhones continue to be world class — and may even topple Samsung in sheer volumes of sales.

For over 30 years, ARM has been saving Apple and at times Apple has been saving ARM. It's a relationship that has made both firms fortunes, and produced devices that are the envy of the world.